The Twelve Factor Scala App

The 12-factor app is a collection of best practices for deploying scalable, maintainable and portable applications in the cloud. It synthesizes the experiences and observations we’ve made at Heroku after hosting and supporting thousands of production Scala applications.

In this article, you’ll learn how to make your deployments more structured, reliable, and safe — characteristics that Scala programmers embrace in their code, but often neglect in deployment. I’ll start with the first five factors and discuss the others in future posts.

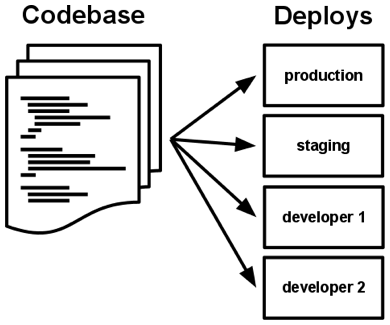

Factor 1: Codebase

Use version control. That part goes without saying I hope. But more specifically, you should have a single version control repository per application. Don’t manually fork your code for deployment, and don’t use a single repository to version different applications.

I see this principle often violated with the use of sbt sub-projects. Sub-projects are great for breaking out libraries from your code, but deployment gets messy when you have a distinct application as a sub-project. It becomes difficult to separate the commit history between applications, and makes isolated rollbacks impossible.

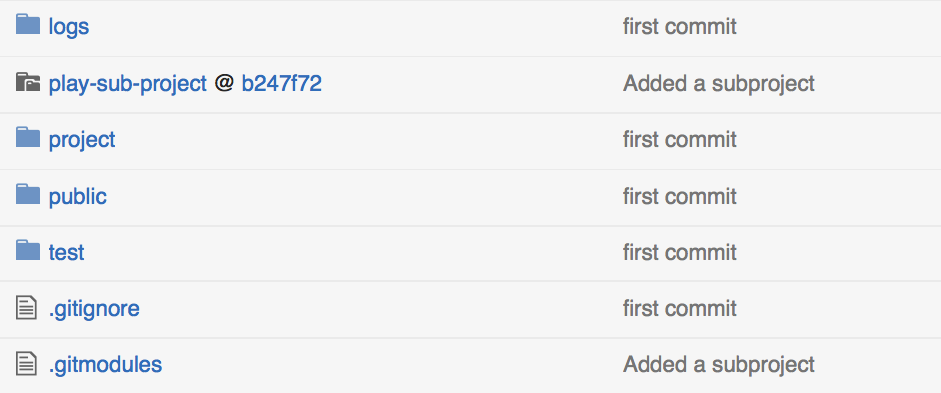

A solution to this problem is Git submodules, which allow you to use sbt sub-projects that are actually their own Git repository. A Git submodule can be added to your project with a command such as:

$ git submodule add https://github.com/jkutner/play-sub-projectThis will create a .gitmodules file in the root directory of your project, and add the secondary application (with it’s own Git repository) as a sub-directory.

Now you can manage both the primary (root directory) application and the secondary (sub-directory) application with the same sbt commands. But you’ll still retain separate version control histories for each.

Factor 2: Dependencies

Don’t check JAR files into version control. Yes, another obvious one. But I have to say these things. It’s worth asking yourself, however, why don’t we check JAR files into Git? The answer is because they become unmanaged. It’s easy to lose track of the dependency’s version, and it makes updating it difficult. It also makes it difficult to pull the dependency into your application because it sits outside of your standard mechanisms (such as Ivy and Maven).

Ultimately, these are the same reasons we want to avoid any kind of global dependency, such as a system library or even a .m2 directory.

Your ~/.m2 and ~/.ivy2 directories are great for development. They prevent the epic download of the Internet every time you spin up a new application. But in production, these global repositories make an application less self-contained, and less portable because the app is more reliant on the underlying platform.

Before deploying to production, you should vendor your dependencies. Vendoring is the process of moving the JAR files your application needs at runtime into your target/ directory. The sbt-native-packager plugin,

which is include by default when using Play Framework, does this for you with the sbt stage command.

Factor 3: Configuration

Don’t check your passwords into version control. Another one for the dummies right? Or is it? Most people know not to check personal passwords into Git, but very often I find that database credentials, Amazon access tokens and other private information is stored in a version control repository. This is a problem not only for security, but also for portability because it makes it difficult to deploy your application into new environments that are not pre-configured.

Your configuration, the things that change between environments (thus, this does not include you conf/routes), should be strictly seperated from your code. Configuration belongs in the environment as environment variables. That’s what their for, after all.

A good example is your database connection parameters. Don’t use a multitude of config files to store all the URLs, usernames, and passwords for each of the databases in your dev, stage, UAT and production environments. That makes your application brittle. Instead, store the database URL as an environment variable. You can access it like this in code:

System.getenv("DATABASE_URL")Or like this in your conf/application.conf file:

db.default.url=${DATABASE_URL}Here’s a good litmus test for this factor: can you open source your application without compromising the security of any cedentials?

Factor 4: Backing Services

A backing service is any service an app consumes over the network as part of its normal operation. Examples include datastores (such as MySQL or CouchDB), messaging/queueing systems (such as RabbitMQ or Beanstalkd), SMTP services for outbound email (such as Postfix), and caching systems (such as Memcached).

The code for a 12-factor app makes no distinction between local and third party services. To the app, both are attached resources, accessed via a URL or other locator/credentials stored in the config. A deploy of the twelve-factor app should be able to swap out a local MySQL database with one managed by a third party (such as Amazon RDS) without any changes to the app’s code. Likewise, a local SMTP server could be swapped with a third-party SMTP service (such as Postmark) without code changes. In both cases, only the resource handle in the config needs to change.

Thus, if you are storing connection paramters for your database and other backing services as environment variables, then you’re well on your way to satisfiying this principle.

Factor 5: Build, release, run

Your deployment process should have three discrete steps. Build: compile the code and package artifacts Release: combine your artifacts with the environmental configuration Run: launch the application process

When using a tool such as sbt-native-packager, and cloud-based service such as Heroku, these steps are realized like so:

$ sbt stage

...

$ sbt deployHeroku

...

$ target/universal/stage/bin/my-appThe stage command, which is provided by sbt-native-packager, compiles your code, vendors your dependencies, and packages your application for deployment. The deployHeroku command, which is provided by

the sbt-heroku plugin, releases your app to the cloud. Finally, you can run your application using a bin script that was generated by sbt-native-packager. Heroku does this for you automatically.

Do not run your application in production with a command like sbt run or activator run. These are great development and build tools, but they are totally unnessecary in production. They add a layer of complexitiy and additional dependencies that only cause problems when running your application under the real world pressures of a production environment.

Further reading

If these ideas resonate with you, try deploying your app on Heroku. Here is some documentation:

- Getting Started with Scala on Heroku

- Deploying Scala and Play Applications with the Heroku sbt Plugin

For more information on the 12-factor app, see 12-factor.net. And for more discussion specific to the JVM see James Ward’s excellent post on why Java Doesn’t Suck.

And of course, come see my talk at ScalaDays Amsterdam 2015.